Dear All,

I am now in Goa on the western coast of India. Over the last 2 weeks, I have gotten from exotic Assam to colourful Nagaland, and then pass through messy, dirty Kolkata (no wonder Mother Theresa was there). I have uploaded over 60 photos of my Nagaland trip including the most amazing and colourful Hornbill Festival (simply very National Geographic!). Do check them out at http://twcnomad.blogspot.com OK, here is my Naga story:

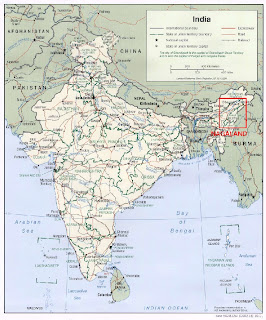

Nagaland: Naked Warriors & Beauty Contest on the India-Myanmar Border

"Uuu Om Uuu Om Uuu Om," the Naga warriors of the Chang tribe flashed their dark elephant hide shields, waved their spears while stamping their feet. Facing them were warriors of a rival clan, looking every bit as menacing as them, especially with the wild boar tasks perched on their headdress, which was topped by a hornbill feather. Hung around the neck of some of these warriors were necklaces with metal carvings of the human head. Some had one, others two or more. The metal carving might look a bit cartoonish, but it represented the number of human heads that warrior had taken in his life. It was only with the taking of a head that one completely removed the soul of the enemy and more importantly, the way a Naga warrior could prove his worth.

Welcome to Nagaland, which Ptolemy in the 3rd century called Land of the Naked, for their half or near-nakedness apart from colourful headdress and other ornamental finery. Over the centuries, the Nagas had been known for their fighting prowess and hardiness, and most of all, their notorious headhunting raids on neighbouring peoples as well as among rival Naga tribes. The Nagas of today, however, are largely a Christian people who sing the gospel on Sundays and put on their tribal costumes only at cultural festivals. Many are highly educated – Nagaland is among the most literate of the Indian states –and many Nagas now work in the IT hubs of Bangalore and Hyderabad.

I spent five days in Nagaland, attending the spectacular Hornbill Festival held annually between 1-7 December. The festival was initiated seven years ago to bring together the 16 tribes of Nagaland (including 14 of Naga ethnic origin), most of whom spoke languages mutually unintelligible and had totally different festivals and customs due to the isolation of the valleys they inhabited, to celebrate their traditional heritage much of which was characterized by exuberant dances and singings, as well as rituals that used to be associated with headhunting raids and war party. It is also a means to unite the Nagas and help shape a common identity among them. I had also attended a beauty pageant (Miss Nagaland 2007) and a heavy metal rock festival, both of which I had never attended or even thought about attending before. More importantly, I had made some great friends and had a good time in this little known region.

---

The Nagas had long been an independent people who had bowed to no one in much of their history, and the Naga tribes as a whole never had any united ruler. Every Naga village is a republic where the headman was elected from among the brave and able. Only the Konyaks have a system of localized kingship which persists till today. For the other 13 Naga tribes living within the borders of the Indian State of Nagaland (and another dozen Naga tribes living across the Indian states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur, and Myanmar's Chin State), each village decided its own destiny. It was once said that when asked who his ruler was, a Naga would thrust his spear into the ground and say, "that is my ruler."

When the British took over the plains of Assam in Northeast India and set up tea plantations to provide good afternoon tea for the Empire, they were upset by the occasional raids conducted by the wild Naga tribes down the hills. So they sent in the tommies, stormed the Naga fortresses and got the chiefs to sign treaties recognizing British sovereignty and agreements to behave themselves. Then the British sent in the missionaries who converted all the Nagas and made them good god fearing Christians who rather spend evenings singing gospel songs and examining the finer points of theology.

After the Japanese marched across British Burma during WWII, they found themselves at the gates of India - the green, foggy rolling hills of what is today Nagaland and Manipur. The British Empire forces were besieged in Imphal, Manipur, while pitch battles took place in Kohima, Nagaland. If Kohima fell, the way was wide open for the Japanese to march down onto the plains of Northern India. It was in Kohima that the British Empire forces defeated the overstretched Japanese after months of battle and began the reconquest of Burma. During the months of battle, tales of courage of the Naga stretchers, supply carriers and helpers spread across the UK. Kohima and the surrounding villages were wiped to the dust. Uncounted numbers of Nagas perished.

After the war, the British decided that they could no longer keep their Empire. As the British prepared for the independence of India, the Nagas suddenly realized they would end up part of India, a country they were never part of. The Nagas were conquered by the British, not the Indians. The Naga Club, an organization set up by eminent Nagas, told the British Government's Simon Commission that their people had "no social affinities with the Hindus or Mussalmans", and if the British were to withdrew, "they should be left alone" like in the ancient days. The Nagas also appealed to the British on account of their war efforts and loyalty to the British, but real politik has always prevailed. The British had their hands full with the chaos and confusion of the Partition of India with Pakistan, not to mention the reconstruction of Britain following the war. Who would be bothered with a few naked tribesmen in a mountainous land faraway?

On 14 August 1947, the same day India became independent, the Nagas declared the independence of the Republic of Nagaland. Initially, the Nagas showed their unhappiness with the new Indian masters through non-cooperation and boycott of elections. However, by 1954, the campaign went violent with full blown insurgency, with arms supplied by Pakistan, China and Burma. The Indian Army entered Nagaland, forced the regrouping of villages in a strategy found successfully in Malaya, i.e., abandonment of villages in more remote areas so as to deny guerrillas of material, food and manpower support, and grouping the population in fewer, easily defended and monitored locations. The strategy had proved successfully to a certain extent but it created enormous suffering and bitterness among Nagas that last till today.

Resistance continued for 50 years till ceasefire in 1997 whereby all Naga factions and the Indians agreed to stop fighting and work for a political solution. Peace has lasted for ten years now and everybody has enjoyed the dividends of peace. Although no solution had been found, as both sides has mutually exclusive goals (Nagas wanted nothing less than independence and Indians would not give up a single inch of Naga soil), nobody wanted the war to resume. Peace is too attractive and seductive.

---

Kohima is a small city built on a mountain ridge, with deep ravines below. To those who have been to Nepal's Everest region, Kohima looked somewhat like Namche Bazar, but much larger and fairly ramshackle in appearance. Perched on the rolling hills of Nagaland, it becomes shrouded with fog almost every afternoon I was there. Kohima has narrow winding roads and its houses are perched between these roads and the naked cliff. An earthquake could be disastrous and most of Kohima's buildings could just crumble and collapse into the abyss beyond. The changes of temperature could be quite drastic, from 10'C at night to 28'C at noon.

What was attractive was not Kohima itself but the friendly, charming Naga people. Mongoloid/Sino-Tibetan in appearance, the Nagas I have met were polite and honest. Unlike in many parts of India spoilt by tourism, the Nagas do not generally try to cheat or over-charge tourists. I did not need to feel guarded all the time against cheats, nor analyse what could be the catch in every seemingly fair transaction. The Nagas are outspoken and transparent, though not without the typical initial reserve one finds among East Asians. During my short stay, I had a good time interacting with them and made a few new friends.

As a Singaporean of Chinese descent, I found many similarities with the Nagas (which they have agreed as well). We are all rice-eaters, unlike the North Indians who prefer roti or pancakes- or bread-like staples. The Nagas would feel unsatisfied not having any rice in a meal. (And yes, the Nagas never call themselves Indians. It's always "we, the Nagas" and "they, the Indians".) Pork is an essential ingredient in both Naga and East Asian cuisines. Like the Cantonese, the Nagas would use anything as ingredients. In fact, one could also find fresh dog meat (an expensive delicacy for special occasions here), silkworms, water beetles, frogs (20 small ones in a plastic bag for Rs 20, about US$0.50) and all sorts of edible insects in the food market.

In Nagaland, everyone thought I was one of them though there were some very minor differences. They tend to be medium to tall, have sharper features than Chinese, and a fairly large proportion of the people I saw on the streets were lean-built. I saw few fat people. Maybe that has something to do with the DNA of a mountain tribal people. Definitely, all the tribal warrior performers I saw at the Festival looked hunky and fit, with tight muscular build.

The Nagas aren't interested in Hindi movies. Korean dramas and movies are a rage in Nagaland today, as in East and Southeast Asia. Korea was the only foreign country to have a booth at the Hornbill Festival site, and a very huge one too, promoting Korean food and pop. My Naga friends told me they could not relate to Indian movies at all – the people look so different and culture totally alien.

Interestingly, the Naga English accent appeared to me to be close to that spoken in Singapore and Malaysia. No Indian accent at all. Must be the Mongoloid tongue that causes that, my Naga friends said. They were very happy to know another person of a similar culture and appearance, and someone who could appreciate their history and current circumstances.

---

The Hornbill Festival was so-named because the hornbill is a bird of common spiritual significance to most Naga tribes. In some tribes, only warriors who had succeeded in bringing back a human head in tribal wars or raids could have a hornbill feather in his headdress. In the Christian Nagaland today, the hornbill feather has become a cultural symbol of the Naga people and is worn on any display that involves the traditional costume.

What impressed me was that most of the performers were young people who took time off work or study to rehearse and perform during this festival. Performers tend to be members of individual tribes' cultural society or student unions. In fact, many of the performers live and work in Kohima but remain in touch with their ancestral tribal roots. Although outwardly the Nagas carry on a modern lifestyle, many are conscious of their unique cultural identity and actively support cultural activities. In contrast, many traditional art forms in Singapore are fast disappearing. Young people in Singapore find traditional opera and dance "uncool" and would rather pursue US/Hollywood cultural norms. My Naga friends agreed with me that their support for traditional pursuits could be linked with their desire to preserve their culture and distinguish themselves from the "Indians".

This year, the festival was officially opened by the British Deputy High Commissioner for Eastern India, and many diplomats and other dignitaries also graced the occasion. I witnessed an interesting exchange between the British defence attaché and a Naga man at my hotel. The Naga, when realizing that the British was a diplomat, welcomed him to Nagaland and thanked him for the many good things the British Empire had introduced to Nagaland, the most important of which was Christianity and English education. The Nagas of today, are more literate than people in many parts of India and speak good English, which allows them to compete internationally.

There is one big bad thing, he said, was that the British did not return sovereignty to the Nagas. Instead, the Nagas, who had fought bravely for the British Empire, were betrayed and had their country abandoned to the alien Indians. Embarrassed, the attaché argued that Britain was in no position to dictate to the Indians or decide on which parts of India should be left out.

The clearly agitated and excited Naga man went on to say that, as a result of British administrative arrangements and abandonment, the Nagas were now left inside different countries and states, such as those living in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Manipur in India, and Chin State of Myanmar. How were the Nagas going to reunite again? Hence, he said that every Naga would educate their children about this and tell them not to forget their aggrieved history and divided lands, and maybe freedom would come one day.

This reminded me of an incident another Naga told me about. When she accompanied a British tourist to a village, an elderly Naga village chief who once served the British soldiers during WWII produced a letter written by a British army officer during the war. The letter acknowledged the destruction of the Naga's village and the contributions of the Naga chief and his villagers, and said that the British Government and Army would certainly compensate and reward them in due course. Nothing had followed ever since and the Nagas now felt totally alienated in a country that they did not consider their own, the village chief informed the British tourist.

---

I visited the Angami village of Khonoma outside Kohima, where huge ancient stone slabs commemorating past local rich who held "feasts of merit" to entertain entire villages, or peace treaties concluded between clans and tribes. Beautiful red and yellow flowers line the village path leading to the dhahus, or meeting places where clan elders discussed important matters such as building of water channels or which enemy village to raid. Beneath the path were spectacular rice terraces stretching beyond the hills.

Khonoma was the last Naga tribal village to surrender to the British and it fell only after a fierce battle. Next to the Baptist church, a memorial commemorated the villagers who died fighting for "Free Nagaland" in reference to the war against the Indians. Forty odd children and perhaps twenty plus adults were singing gospel songs as I past an open air chapel nearby, and they served me tea and cookies. A sense of peacefulness in a village that had seen the many episodes of Naga history.

Not far from Khonoma village was a huge monument perched on a cliffside viewpoint overlooking the rolling hills and deep valleys. This monument, too, commemorated the India-Naga War, as the Nagas called it. On it, a plaque read "Nagas are not Indians. Their territory is not a part of the Indian Union. We shall uphold and defend this unique truth at all costs and always. Khrisanisa Seyie, First President, Federal Republic of Nagaland. 12th July 1956 to 18 February 1959."

These monuments are the very indications of Naga aspirations and desires, no matter how hopeless their cause may be – 2 million Nagas in a emerging superpower India of more than 1 billion. To me, the existence of such monuments, especially the huge one in such a prominent tourist attraction, is also a tribute to India's democracy, which for all its contradictions could accept a monument which advocates for separation from the Indian state.

I asked a few Nagas what they thought of independence or its likelihood. One said independence is impossible for a landlocked land like Nagaland. They would have only two neighbours – a democratic but imperfect India with a totally different culture and race, and a totalitarian, pathetically poor Myanmar inhabited by fellow Mongoloids. He said he would rather be an Indian citizen and take advantage of its growing prosperity.

Another Naga, however, said that the Nagas had always been free and nothing was more precious. Independence is not impossible if all the nationalists could unite and put aside self interest and tribal rivalries. Whatever stand one takes, virtually all the Nagas I met are proud of their cultural heritage and conscious of the difference between them and the "Indians" – the latter always spoken as though the Nagas are not Indians.

---

Life is always tough for civilians in any insurgency, as they face the wrath of all sides to the conflict. The Naga conflict of 1947-1997 was no different. I was told that some insurgents behaved like gangsters and demanded for material and monetary support failing which there would be consequences. Apart from bombing raids and human rights abuses, Indian soldiers had behaved like an occupation army, enforcing curfews and treated Nagas in nasty, racist manner. I was told that they often bullied Nagas who passed army checkpoints, sometimes even forcing elderly men to do push-ups on the road. Such actions generated tremendous illwill and hatred for the Indians, and one of my Naga friends told me how angry he was whenever he encountered such injustice. He had to suppress his anger in case he did anything stupid in public.

Since the ceasefire in 1997, Indian soldiers no longer misbehaved. Huge signboards outside the prominent downtown barracks of the Assam Rifles proclaimed themselves as "Friends of the Hill People". In fact, many of the soldiers I saw patrolling the streets and guarding the main roads and festival grounds are young, smartly dressed Nagas, who have joined the elite Indian Reserve Force. How things have changed!

No longer are there conflicts between the Indian Army and the Naga guerrillas. There are, however, skirmishes between the Naga factions, and occasionally between the Nagas and a rival ethnic group called the Kukis who are also found in Manipur and Assam states. The first Naga guerrilla group was the Federal Government of Nagaland (FGN) which launched its insurgency in 1956. It later split and another rival FGN army was formed.

Since the 1960s, the key forces fighting the Indians have been the Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), a group whose original aim was the setting up of a Marxist Nagaland run on "original" Christian and socialist principles. The NSCN later split into rival factions named after its rival leaders, NSCN (Isak-Mulivah) and NSCN (Khaplang), named after Isak, Mulivah and Khaplang respectively. The split occurred in the 1960s and both NSCN groups have fought each other as vigorously as they fought the Indians. There are no major differences in ideology between them, just personality of the leaders. NSCN (I-M) is the stronger one at the moment.

Despite officially being illegal organizations, since 1997, both NSCN factions have operated rather openly. Their camps have been established at open, prominent sites, and their key commanders are known to all. In fact, their telephone numbers were published in the papers so that Nagas could call in to report criminals and NSCN would dispense revolutionary justice, i.e., a bullet to be lodged in the criminal's head.

The NSCN were mentioned in the papers everyday, in terms which to an outsider like me seemed bizarre. On one hand, it was obvious that they were illegal underground organizations and they operated largely in semi-secret basis even from the tone of the reports, with references to "according to underground sources". On the other hand, they were regularly consulted by mainstream politicians and bureaucrats for their views. An example was a report about "local functionaries" of NSCN being consulted by police over the movements of certain persons. When I was there, public organizations made statements appealing to the two NSCN factions to make peace for national interest and so as to unite all Nagaland within the same entity.

I asked a Naga where NSCN members are these days. In the deep jungles where they fight the guerrilla war? No, the freedom fighters are everywhere, he said. In the towns, villages and jungle, and they include professionals, bureaucrats, workers, farmers and even in the police and army as well. And you never knew who is a NSCN member…I wondered if he is one. Indeed they sounded like the secret cell groups that Viet Cong had across South Vietnam during the Vietnam War, and the similar prevalence of Shiite insurgents among Iraqi society and government today.

The NSCN factions function like a parallel state within a state. They collect taxes (yes, called "donations") from local businesses and as mentioned earlier, dispense justice, albeit rough and sometimes unfair ones. This reminded me of the Maoists in Nepal now. The difference is that, the Maoists are on the threshold of total victory. I am not sure about the Naga rebels, or freedom fighters as many Nagas call them.

Naga society is a highly politicized one. The newspapers are full of press release and statements about political events by organizations whose names don't sound political at all. For instance, issues such as unity between the NSCN factions and attempted assassination on a former chief minister had elicited statements from organizations ranging from all kinds of tribal and district student unions, women's associations of individual tribes or districts to professional associations. I wonder if these organizations have any time for the purposes they were set up for.

In addition, I also realized that Nagas like to form organizations or societies. A typical Naga organization is formed from any permutation of three words: The first is either the name of a district, village or tribe; the second is the organization type, be it professional or social (e.g., lawyers, accountants, welfare, sports, cultural, student or women); and third, society, union, association and the like. Given that Nagaland has 16 tribes and 11 districts, imagine the number of organizations you can form even without counting the number of villages.

---

A major local newspaper theme is that of Nagalim, a proposed Greater Nagaland which also includes territories where other Nagas live, such as those in the Indian states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur, and Myanmar's Chin State. The Nagaland State Assembly actually passed a resolution a few years ago calling for the unification of all Naga lands. Local papers seemed to suggest such a goal was entirely feasible. I cannot imagine what would be the reaction of non-Nagas living in the extended territory Nagas claim as their own, or of the Myanmar Government on demands for the incorporation of Chin State into Nagalim. The whole thing seemed to me an exercise of the impossible.

---

Nagaland produces excellent mandarin oranges. They tasted so good that I bought more at the Nagaland Orange Festival which was held in conjunction with the Hornbill Festival. These oranges were supposedly organic and hence their skin was somewhat rough and unappealing. But they tasted wonderful. Potentially Nagaland could sell the oranges outside the state or even export. However, roads within the state and out of the state are horrendous and the oranges would not reach the markets in time.

The most important road in the state is the one linking Dimapur, Nagaland's largest city located on the border with Assam, and Kohima, the state capital. Yet this narrow winding road, hugging treacherous cliff sides at a large portion of the journey, disintegrates into mud and dirt at many stretches. I was told there were even occasional landslides. The other intra-state roads are worse, such that in order to travel from Kohima to Mon at the northern end of Nagaland, it is better to travel out to the neighbouring state of Assam (which has better roads) and then re-enter Nagaland at the north (instead of travelling direct on the Kohima-Mon road which lies within Nagaland territory).

The problem with the Nagaland economy is that it has some potential in areas such as commercial agriculture/horticulture and hydroelectric power, but not enough to power a tiger economy. Furthermore, agriculture is not an attractive sector for the many young highly educated Nagas produced by a culture that places emphasis on education, yet another legacy of the Christian missionaries that converted the Nagas in the 19th century. The Naga government, highly subsidized by the Indian central government, is the main employer in the state. One of its challenges would be to find employment for young Nagas so that they would not channel their energies into more political activity that would aggravate the already unstable political environment.

Tourism is potentially a growth area for Nagaland. Yet, existing rules that require permits from both foreigners and Indians are complicated and time-consuming, thus deterring more visitors. For instance, for a permit to be issued, foreigners need to be in a guided tour in groups with minimum four members, or a married couple (certificates to be produced as evidence). Failing that, such as in my case as a solo visitor, no-objection certificates would need to be obtained from the Nagaland State Department of Home Affairs, Indian Union Department of Home Affairs and the Nagaland Resident Commissioner in New Delhi. The whole process takes weeks if not a month or more.

The lack of hotel infrastructure presents another major problem for tourism development here. There aren't enough hotels not to mention good standard ones. The Hornbill Festival is the peak tourism season here and all rooms in Kohima were booked. Yet, only 400 visitor permits were issued for the festival duration of 7 days. No matter how attractive the festival may be, Kohima cannot accommodate more than a few hundred visitors at the moment.

---

I dropped by the Miss Nagaland 2007 competition held in an assembly hall next to my hotel. When asked what they most hope for in the new year, the newly crowned Miss Nagaland said it was peace, for without peace you could have anything else. This was also the constant theme in the local papers as well as in the speech of the Indian minister who attended the second day of the Hornbill Festival. Negotiations between the Naga groups and the Indian government have gone nowhere because of their drastically different positions. The Naga factions remain deeply divided among themselves. Naga activists are also obsessed with the theme of unification of all Nagas, which implies annexation of lands belonging to other states and tribes, something those states and tribes bitterly oppose. But let's hope that all these parties would continue talking and never take up arms, for armed conflict would be disastrous and miserable for ordinary people. I had a wonderful time in Nagaland and certainly hope to return some day.

For those who are interested in visiting Nagaland and other parts of Northeast India, you may wish to get in touch with these agencies (and mention my name if you wish):

Liza World Travel: www.lizaworldtravels.com

Tribal Disovery: www.tribaldiscovery.com

Yes, don't forget to check out my amazing Hornbill Festival photos at http://twcnomad.blogspot.com

Have a good weekend!

Wee Cheng

Goa, western India

Comments

against British invasion and Christian

conversion. Angami braves of Khonoma, Mezoma and Kekrüma fought against

British rule and Christian missionaries for se

veral years in first half of the nineteen

century. The Chakhesang Nagas of Thev

opisumi village fought against Christian

conversion and church sponsored Naga Nati

onal Council (NNC) led by A.Z. Phizo –

who demanded complete secession from

Bharatvarsh. Haipou Jadonang – a

Rongmei Naga from Manipur who led a stro

ng resistance to British expansion and

missionary menace, was hung on 29

th

August 1931. Rani Gaid

inliu – then a girl of

16 years led the movement called Zeliangro

ng Heraka Movement to protect the

sovereignty of the country and defend indigeno

us Hindu faith. Even A. Z. Phizo who

hailed from Khonoma village assisted Indi

an National Army (INA) led by Netaji

Subhsh Chandra Bose in the Kohima war du

ring Second World War to defeat British

invaders. Even after this resistance, Britis

h could establish their

rule over Naga Hills

area and pushed American and British Ch

ristian missionaries into Nagaland under

Army protection and Government support. The forced conversion to Christianity and

expansion of British rule advanced together

. After the grand success in dividing the

country by creating East and West Pakistan

, the Britishers picked up Phizo and NNC

cohorts to create a Christain

country in Northeast Bharat.

Firstly, British officers employed Christ

ian missionaries to convert Nagas and then,

they (British rulers) asked converted Na

gas (Phizo and NNC

militants) to start

inquisition against those Nagas who refused

to convert to Christianity and support

British policy after 1947 so that a Christian

solidarity could be es

tablished with USA

and UK by the initiative of American an

d British Baptist Christian Church for the

formation of Christian Sovereign Nagaland

. Phizo who supported Army of Subhash

Chandra Bose and fought against British

army, joined the British bandwagon after

conversion to Christianity and waged a

war on Bhratvarsh to secede from the

country and started Christian inquisitions in

support of Christian crusade to convert

all Nagas to please his British masters.

Anybody who expressed different opinion

was brutally killed. NNC and church were

all the same. Overnight, churches opened

in even remote areas, which became

shelter place for guerillas of NNC.

Missionaries acted as informers against

army movements and against those Nagas

who did not support NNC uprising and Christ

ian inquisition jointly operated by NNC

and church. This was the reason that Ra

ni Gaidinliu and her Zeliangrong Heraka

(Hindus) movement was the prime target of

NNC and Church. They (NNC & Church)

were after the head of Rani Gaidinliu –

the freedom fighter. British missionary –

Rev. Michael Scott became friend, philosop

her and guide of Phiz

o and NNC rebellion.

This British reverend supplied lethal we

apons packed in Red Cross boxes to NNC

militants. The Church formed several NGOs

which acted as host to NNC guerillas and

Christian crusade. Government of Bh

aratvarsh under Pt. Nehru couldn’t pay

requisite attention to what was being do

ne against the country by NNC and Church

combine